The Victorians: sentimental and mawkish? Or inventors of the stiff upper lip?

Lots of men nowadays feel they aren’t allowed to cry, generally because gender roles (gotta be strong, can’t be a big girl’s blouse). So I was curious to find out if men in Victorian times felt the same.

One of my favourite examples of the stiff upper lip is in Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day. Stephens’ mother dies, and his father (a butler) simply reinforces his upper lip with cast iron and gets on with serving the sherry. All day. Dry-eyed. Not a tremor in his measured tones. Possibly his hands shake a tiny bit towards evening. Possibly not even that. That scene in the book occurs in the late Victorian period, and, while fictional, it’s utterly convincing.

Another of my all-time faves is Captain Lawrence Oates’ famous “I am just going outside and may be some time” (1912, so admittedly not Victorian). He was, of course, hobbling out on gangrenous feet to certain death in a blizzard. And that one’s probably true.

I’m somewhat familiar with the stiff upper lip on a personal level, having been brought up by English parents who were children during the Second World War. Though in their case it’s more a horror of ‘making a fuss’. They’re not shrinking violets. They’ll stand up for themselves – or anyone, for that matter – if they think an injustice is occurring. But one doesn’t complain if faced with a fait accompli. One doesn’t let the side down. One puts on a brave face. Even if one’s foot is about to fall off.

When I starting reading about the Victorian period I thought the men would, almost exclusively, have upper lips of steel.

But in fact, not so:

- When Charles Dickens got back from a trip to America in 1842, his friend John Forster was so happy to see him he jumped into Dicken’s carriage and began to cry

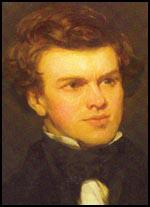

- When Dickens wrote The Chimes (one of his Christmas stories) there were men crying at every turn. Dickens wrote it in a bit of a lather and once finished “had what women call ‘a really good cry’”. He read it aloud to his friend Macready, who reacted by “undisguisedly sobbing, and crying on the sofa”. Dickens was delighted (he loved making people cry) and promptly arranged another reading. This larger reading was sketched by Dickens’ friend Maclise (see above). It shows two of the men crying openly, and I reckon some of the others have wobbly chins. Writing to Dickens’ wife, Maclise mentions the “floods of tears”. Dickens told his sister Fanny that even the printers had “laughed and cried over it”. And all that was just for one story. Tiny Tim, anyone?

- In 1853, the painter John Everett Millais was hopelessly in love with John Ruskin’s wife, Effie. Ruskin describes Millais ‘lying crying upon his bed like a child – or rather with that bitterness which is only in a man’s grief’ – a remark that implies he was familiar with men’s tears. Millais, unable to admit the truth, told Ruskin he was heart-broken because his great friend Holman Hunt was leaving for Syria. Ruskin does seem to have found this a bit over the top, but he wrote to Hunt anyway telling him he’d better not go. Millais had to quickly write to Hunt as well and tell him to carry on

- Joseph Paxton, the Duke of Devonshire’s tireless gardener, friend and all-round genius, wept when he had to say goodbye to the Duke and his retinue after a trip around the continent (Paxton had to go home to England)

- And of course there are various accounts of funerals (the Duke of Wellington’s, in 1852, springs to mind) where it sounds as though the entire population of London was in tears – men, dogs and horses included.

These examples are interesting because they cast the myth of the supressed Victorian man in a new light. Obviously, some men did cry, at least amongst friends – and no-one seems to have thought it unmanly. I don’t know if it’s telling that Dickens and Millais and their friends were middle-class, and from artistic/literary circles. Would noble or working class men have cried as readily? The printers certainly did. And Paxton was from working class stock, though he’d certainly risen in the world by the time he went travelling with the Duke.

My examples are earlyish-Victorian, because that’s the period I’m reading about (because that’s when the books I’m writing are set). Did displays of male emotion become less acceptable as the century drew on? Perhaps. It certainly sounds as if life under Victoria became less bawdy than it had been under previous monarchs, so perhaps there was a cultural shift towards stiff upper lips too?

Got any good examples of Victorian men crying? Or of marvellous stiff upper lips? Please share, I’d love to hear from you. And please give dates if you can.

Hi Lee. Thanks for an illuminating post on a subject that has often piqued my interest. Your Millais example puts me in mind of his and Hunt’s tearful farewell at the train station when Hunt left for Syria, and the way Hunt recalled this as almost a sublime experience is v interesting. Another example – I’m writing a book on the historian William Napier (1785-1860) who was a famous crier. This was described positively by a man of younger generation in an 1864 biography, yet with reservations suggesting male weeping was becoming problematic or at least more complex as century wore on. Another: an account in The Times of Prince Albert’s brother at Albert’s funeral describes him & other men & boys in tears while women praised for “fortitude” (which I take to be not crying). Thomas Dixon’s book “Weeping Britannia” has lots more as you may know.

LikeLike

Hi Eleanor – ooh, nice examples! I love Hunt’s sublime experience at the train station. So interesting that the whole men crying thing really does seem to have become less acceptable as the century wore on. Can’t wait to read your book about Napier (a ‘famous crier’ – I like him already!) Also thanks heaps for the tip about ‘Weeping Britannia’ which is clearly leaving a gaping hole in my library. Must get a copy. Stat.

LikeLike